Aaron William Moore, University of Edinburgh

Summary

In order to understand why so many ordinary people supported communism in China, it is necessary to look at personal records like diaries. Increasing literacy through education greatly aided the Party’s efforts to conduct ‘thought work’, enact mass mobilisation campaigns across China, and generally bring about social change through its orthodox political ideology and practices. Although surveyed diary writing can be thought of as a form of cultural work, it was also a tool used by authors to learn about Chinese communism and their place in the new society.Introduction

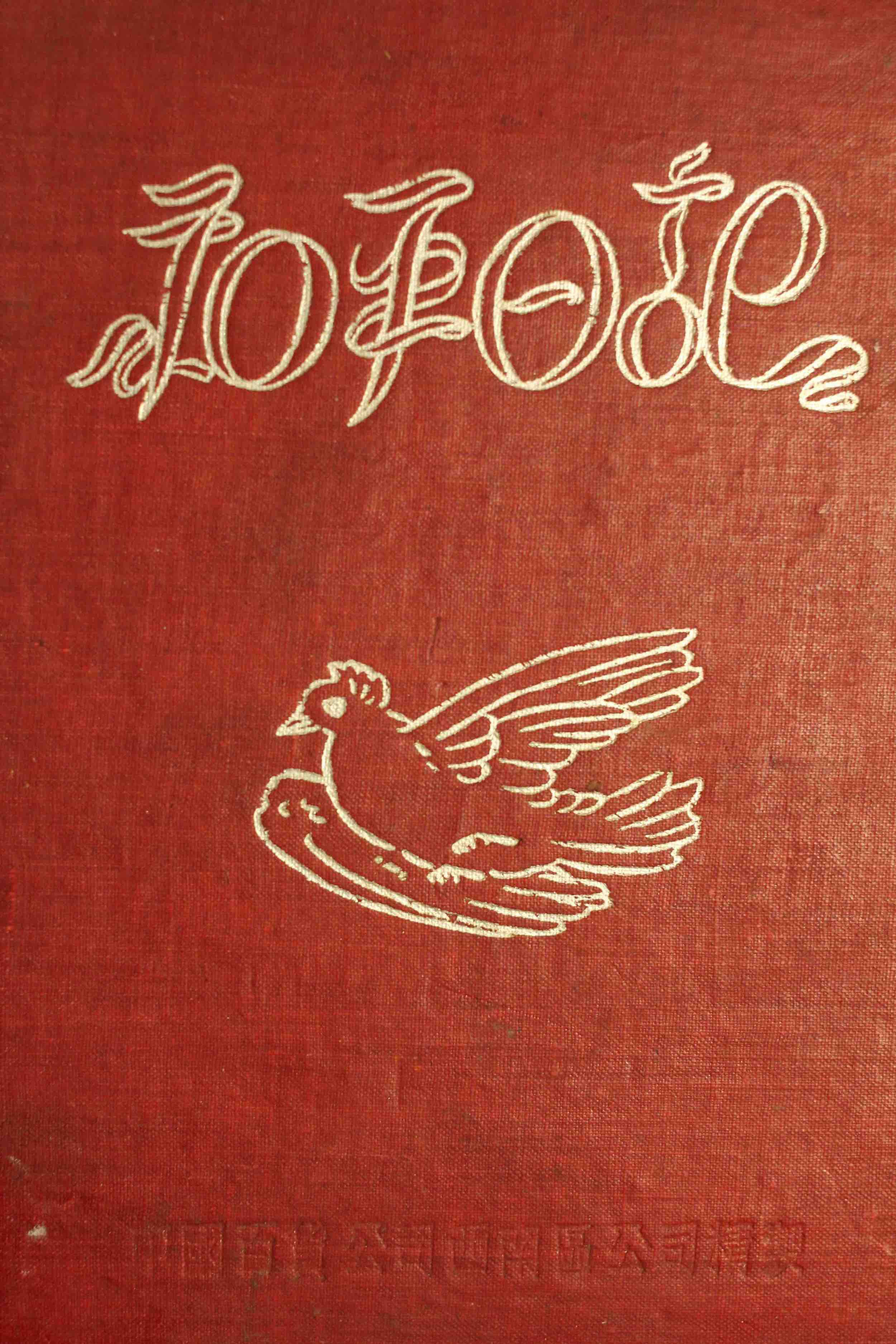

The generation that lived through the early years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is gradually passing away, leaving behind personal objects that represent its experience, and few objects hold as much fascination in this regard as the personal diary. Personal diaries of the early PRC period (1949-1966), before the Cultural Revolution began, were small books with titles such as ‘Peace Diary’ [see ⧉source: Peace diary, also depicted to the left], ‘Red Star Diary’, or ‘Work and Study’ [see ⧉source: Work and Study diary]. Those documents are an important resource for understanding how ordinary people understood communism as an ideology, as well as how they made its tenets part of their daily life. Diary writing was not an entirely modern technology for Chinese people, as the genre enjoyed an ancient history almost as old as China itself. Nevertheless, a number of changes occurred during the Republican Era (1911-1949), particularly following the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) successful Northern Expedition (1926-1928) to defeat warlordism and unify the country. The KMT government aimed to create a self-disciplined populace by using the diary as a tool, and this only accelerated during the early PRC, when diaries became more widespread.

Despite the popular view of modern China as a place populated by illiterate peasants, the KMT and PRC efforts made the diary an important if overlooked part of Chinese life. In order to construct a biography of the modern Chinese diary, it will be necessary to examine its Republican origins, as well as how it was more fully popularised in the early PRC period. The authors of PRC diaries tended to be educated citizens based in or near urban centres, working in fields such as accounting, engineering, public works, teaching, or as cadres overseeing land reform. The diaries could be purchased, received as gifts from schoolmates, or given by comrades in the workplace for the purposes of personal and group study; many include dedications from friends inside the front cover. Diarists used their personal accounts as tools to learn the new language of Chinese communism and how to navigate the political system. As small, cheap, and portable objects, they were never far from the author’s body.

Origins of the Modern Diary in the Chinese Republic, 1911-1926

Diaries of the early Republican Era were still quite similar to early modern autobiographical documents (e.g., from the Ming and Qing Dynasties), including bureaucratic diaries and scholarly introductions to commentaries on the classics. Still, in contrast to the life writing of early modern gentry, the modern era brought a new focus on the lives of ordinary people. Literary figures such as Lu Xun 鲁迅 and Ding Ling 丁玲 introduced to the reading public the notion that the personal experience of the everyday had aesthetic and cultural value. Simultaneous to literary trends that featured personal narratives, bureaucratic, business, and military figures composed and occasionally published diaries that teachers, managers, and army academy officers used to instruct the youth of the Republican Era in the principles of self-discipline. Even in the absence of strong central government coordination, army officer academies including Huangpu, Baoding, and the Jiangwutang (黄埔, 保定, 讲武堂) all encouraged disciplined diary writing as a form of modernisation in an age of ‘military science’. Furthermore, officers and bureaucrats trained in Japan, which had launched a programme of military modernisation after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, would have been exposed to the pervasive personal and professional record keeping there.

Early Republican diaries were still written with brush and inkwell, over paper that was produced using the same technology that dominated manufacturing in the late Qing. The language was unpunctuated and in classical Chinese. Consequently, the authors needed to possess leisure time before a desk with all of the material accoutrement of a scholar or literati, even if they were modern military men.

Nevertheless, in the early twentieth century Chinese educators were closely following the Japanese ‘daily life record movement’ (seikatsu tsuzurikata undō 生活綴方運動) and the Soviet ‘school diaries’ (shkolny dnevnik, школьный дневник) that were becoming common in classrooms there, as well as the diaries used in Western religious schools that were based in China [see ⧉source: The Blue Book]. Although the ideologies that informed diarists in each context were extremely different, in each case children were encouraged to record their ‘innermost thoughts’ honestly, consistently, and earnestly, which suggested that Japanese, Soviet, Chinese, and Western teachers all believed that diary writing had disciplinary and pedagogical value. Still, the diaries of schoolchildren, government officials, businessmen, or military officers were not ‘personal’ in the sense that favoured private family confessions over public professional personae; they were primarily concerned with documenting facts and mastering the language salient to their social position. Whether these distinctions—public and private, professional and personal—are meaningful in any cultural context is a subject of scholarly debate.

Rapid Change under the Chinese Nationalist Party Rule, 1927-1949

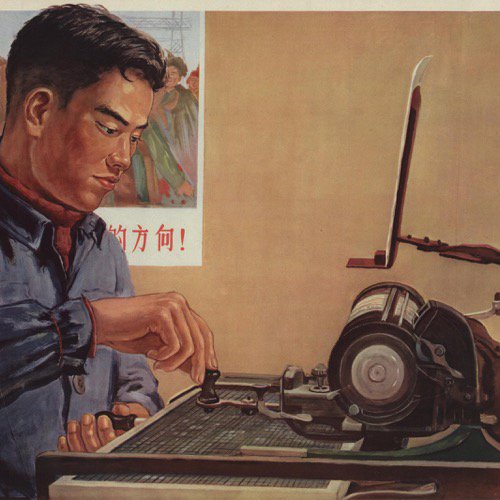

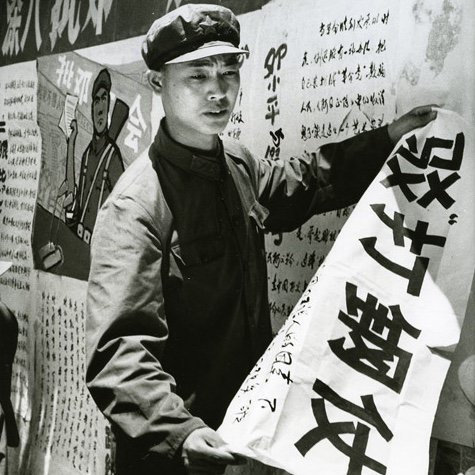

Soviet influence on the re-organisation of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) leading up to, and including, the Northern Expedition (1926-8) changed the nature of the diary significantly. Political training was now an important component of KMT military and party organisation, and for this purpose the diary was useful. Chinese officers shared diary accounts amongst each other (chuanyue 传阅), had clerks (wenguan 文官) transcribe them using mimeograph boards, and contributed these accounts to state archives in a system that was more comprehensive than that of the United States armed forces of the same period. Still, many of the existent records suffered damage through Chinese history, and are only available in hand-written fragments [see ⧉source: Work diary].

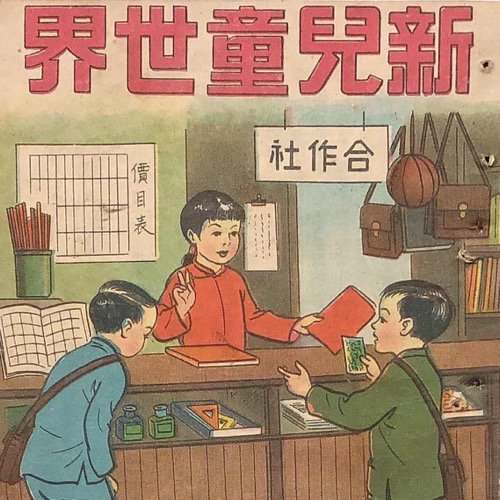

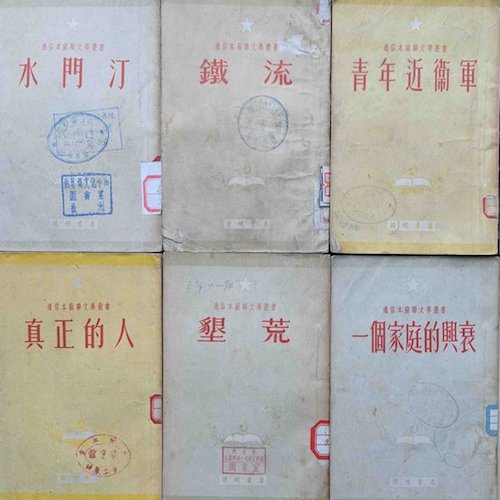

Meanwhile, schoolchildren across Nationalist China were encouraged to imitate famous authors by recording their daily lives in diary format. Primers for composition exercises (zuowen 作文) included diary writing, and teachers published exemplary student diaries (mofan riji 模范日记, see ⧉source: Model diaries for schoolgirls) up to and including the period of Japanese occupation (1937-1945). By the 1940s, the KMT asked officers, bureaucrats, and important party members to document their work in diary form; this met with mixed results, because the KMT found itself beset by Japanese encirclement during WWII, and then unreliable US support, aggressive communist expansion, and continually collapsing public finances after 1945. Nevertheless, Chinese war reportage literature (baogao wenxue 报告文学) had already introduced the idea that the ordinary soldier, citizen, and refugee’s experience could, and should, be textualised and published for popular consumption.

At the same time, the material conditions for producing and distributing blank diaries improved dramatically. Kraft paper production used pulped wood to make cheap and durable paper by 1900, and in the early 1930s recovery boilers made the process scalable at the national level. After the invention of machine bookbinding in the 1850s, technologies to produce cheap and durable blank diaries diffused quickly around the world. Consequently, by the 1930s Chinese soldiers, students, and businessmen could, like their Soviet and Japanese counterparts, carry robust pocket diaries wherever they needed to be. Rubber cartridge fountain pens, which became increasingly widespread in the 1920s, made writing in small pocket notebooks far easier than it had been in the late Qing and early Republican Era. In 1931, Zhou Jingting 周荊庭 had launched large scale domestic production of fountain pens in Shanghai, and his company Huafu (华孚) led the way in writing implement manufacture into the post-1949 era [see ⧉source: New citizen's fountain pen]. By the time of the Chinese Communist Party's consolidation of its power on mainland China, the basic technologies of diary production, surveillance, and social discipline were already in place, waiting to be re-purposed by a more effective political organisation than the KMT.

Re-Making the Personal Diary after the 1949 Communist Revolution

After the success of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1949, mass industrial production of cheaply-bound and robust pocket diaries was easy to launch, there was a cultural acceptance of the importance of diary writing for capturing historical experience, and various organisations, from the military academy to the schoolhouse, used the diary to teach citizens proper self-discipline. For the CCP, which encouraged Chinese people to use study sessions to inculcate lessons from the mass line (qunzhong luxian, 群众路线), the diary was a tool that was ready for new application.

Local publishers in former KMT strongholds, including Shanghai, Chongqing, Wuhan, and Kunming, continued to produce cheap blank diaries for mass consumption, but there were some superficial changes as these formerly private companies drew closer to the government. There were several kinds of mass-produced blank diaries during the 1950s and early 1960s, many of which were re-designed from previous models. For example, from the very beginning of the People’s Republic, ‘Red Star Diaries’ (hongxing riji, 红星日记), aimed at young people (qingnian, 青年), were published by the Shanghai Xiangjixing Paper Company [see ⧉source: Red star diary]. Diaries entitled ‘Work and Study’ (gongzuo yu xuexi, 工作与学习) were extremely common, usually published by the Shanghai General Merchandise Corporation (Shanghai/Zhongguo baihuo gongsi, 上海/中国百货公司), although they were also apparently subsidized by the bond department of the Bank of China. From about 1952, ‘Democracy Diaries’ (Minzhu riji, 民主日记), which were inspired by Mao’s 1940 ‘On New Democracy’ and calls to ‘democratise the workplace’, emerged from Shanghai’s Yaguang Stationary, but other publishers appear to have produced diaries with this title as well. Some diary formats briefly persisted from the Nationalist period, such as the popular ‘Diary Record of Achievements’ (Baicheng riji, 百成日记), which was a staple pocket notebook for Zhejiang and Jiangsu educated people [see ⧉source: Diary Record of Achievements]. Much like a transport system or a schoolhouse, the diary was adaptable for almost any modern political order.

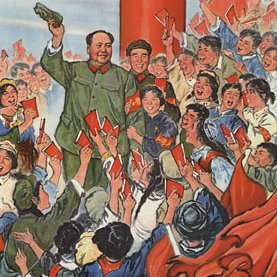

Most PRC diaries eventually contained a portrait of Mao Zedong and party slogans that were important for a particular year, such as ‘Resist the Americans, Aid the Koreans’ during the Korean War and ‘Let One Hundred Flowers Bloom’ during the Hundred Flowers campaign. Paratextual inscriptions suggest that many were gifts given to university graduates, but also ‘delinquent youth’ in urban ‘work-study’ rehabilitation centres or handed out among members of collective farms and urban work groups [see ⧉source: People's diary]. In short, the diary served as a tool for individuals to develop articulations for publicly participating in revolutionary mass movements.

Using the Personal Diary in the Early PRC, 1949-1966

Diarists of the early PRC were preoccupied with finding their place in the new political order, which required mastering a new language as a means of adopting a revolutionary subjectivity. Consequently, perhaps, Liu Shaoqi’s How to Be a Good Communist (Lun gongchandangyuan de xiuyang 论共产党员的修养, 1949 / 1962) reiterated the Republican Era call for ‘self-discipline’ (ziwo xiuyang 自我修养) as a means to this end; later critics would identify this as the ‘ideal nation [made by] the ownership class’ (lixiangguo … zichanjieji guojia 理想国 … 资产阶级国家), because its focus on individual subjectivity obfuscated class conflict and failed to locate true democracy as an emergent property of working class consciousness.1 One of the central contradictions of early Chinese communism was that mass subjectivity had to be established through individual ‘work and study’, for which the personal diary was a useful tool but also a potential site for heterodox ideology. Using the diary as a workspace for hammering out a revolutionary subjectivity was particularly important for educated Chinese people in areas formerly controlled by the KMT. At the beginning of the Five Antis Campaign in 1952, one engineer in Nanjing wrote in his diary, entitled 'The Age of Greatness' [see ⧉source: The Age of Greatness]:

'Following the Three Antis Campaign, every one of us have investigated our pasts to see if we have been influenced by any sort of attack by capitalist class thinking. So, what’s the situation? After going through the Three Antis, three years following liberation (1949), have you recognised those facts, including the reality that the capitalist class is trying to seduce us? Following the Three Antis, have you reached that thorough understanding of the working class, and the Party? …

We must eliminate all poisons from the old system and way of doing things (including the leadership position of the capitalist class). In order to have the ideology (sixiang 思想) of the workers lead us, we must correct our thoughts (sixiang gaizao 思想改造) and establish a working class mindset (sixiang 思想)—this will complete the democratic revolution. Through the Five Antis, we will establish a democratic, new workplace. At the level of consciousness (sixiang 思想), we will start anew and draw a clear line (huaqing jiexian 划清界线) [with the past].

Thus, the diary could inculcate revolutionary communist consciousness as it had revolutionary nationalism for the pre-1949 KMT: namely, through the proactive efforts of the individual diarist. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, diarists scribbled records of important conversations, minutes of workplace meetings, notes on Marxist canonical works, and personal reflections in an effort to find their proper place among the masses.

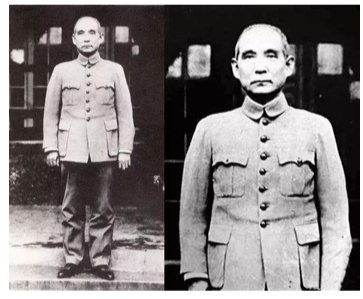

An Intimate Friend? The PRC Diary as Material Object

Although the contents of the diary are of paramount interest, the materiality of these objects should not be ignored; for diary writers, this small booklet was like a lamprey that was rarely deadly but never fully detached from the body. Diaries ranged from 18cm x 13cm x 2cm to 13cm x 10cm x 1.5cm, but the vast majority produced in the early PRC were of the former dimensions, which were exactly the same as blank diaries published at the latter part of the Republican Era. Blank diaries would fit within the external side-pocket of a ‘Mao Suit’ (actually a ‘Sun Yat-sen Suit’, based on the early leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party, Zhongshan-zhuang 中山装, see ⧉source: Sun Yatsen/ Mao suit also depicted to the right); this meant that personal diaries could be carried on one’s person at all times, along with a pencil or fountain pen.

The pocket diary was not meant to be hidden or completely private, but there is no evidence that they were routinely reviewed as a KMT military, school, or bureaucratic diary would have been; nevertheless, they could be untrustworthy friends: some were read at later dates in the 1960s by ‘investigation committees’ (zhuang’anzu 专案组) and used as evidence against the authors. These committee marks show us that the diaries were not ‘private’ in the sense that the authors had to present them to authorities if they were under investigation for a crime. Particularly during periods of anti-corruption campaigns or other efforts, either local or national, ‘investigation committees’ had considerable power and authority to collect and review personal documents in the pursuit of conviction. Beyond that, early PRC diary entries strongly suggest that they were visibly deployed by authors during public meetings, workplace debates, and study group sessions. It is wrong to think of them as private confessionals, but it is also misleading to suggest that they are unreliable or purely public records.

Changes in printing and writing technology realised the dream of the earlier KMT regime to make diary writing ubiquitous as a tool for self-discipline in China. New processes for pulp paper production and modern cloth binding meant that, since the 1930s, robust personal diaries had become cheaply accessible to millions of Chinese people. The widespread use of rubber ink cartridges allowed peripatetic diary authors from KMT era soldiers to PRC era land reform cadres to write without fear of breaking their instruments. Unlike many of the Republican Era blank diaries, PRC books included colour illustrations, calligraphic inscriptions, portrait photography, and artfully designed covers. These elements were present in 1930s Chinese publishing, but the PRC materials are best understood as a renaissance of domestic production following recovery from Japanese occupation and subsequent civil war (1946-1949). Nevertheless, the documentary record suggests that diarists were typically well educated people in the early PRC era, including engineers, cadres, university students, scientists, industrial managers, and professional writers.

The combination of affordability and robustness of blank diaries, the importance of self-discipline in the creation of socialism in China, and the methodology of using study groups to overcome contradictions (such as the need for expertise and the democratisation of the workplace), all converged to make the diary an important material object of Chinese modernity after 1949. As Michael Schoenhals has shown, they were neither wholly public documents nor private confessionals, but also important tools in the creation of social knowledge by the state apparatus.2 Despite the risks one took in keeping one, the personal diary has been one of the most important objects through which literate citizens have processed public discourse and found their place in the socio-political order from the Republican Era to the People’s Republic.

Footnotes

Red Flag Magazine (Hongqi zazhi bianjibu 红旗杂志编辑部) and People's Daily (Renmin ribao bianjibu 人民日报编辑部) (eds.), The Harm in "Self-Cultivation" Is a Dictatorship of the Treasonous Bourgeoisie (“Xiuyang” de yaohai shi beipan wuchan jieji zhuanzheng 《修养》的要害是背叛物产阶级专政), Kunming: Renmin chubanshe, 8 May 1967.

Michael Schoenhals, 'Diaries' Lund University Source Pages on Social history of China, 1949–1979 (https://projekt.ht.lu.se/en/rereso/sources/diaries/).

Sources

- ⧉ IMAGE

- 文 TEXT

- ▸ VIDEO

- ♪ AUDIO

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: Peace Diary

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: Work And Study Diary

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: The Blue Book

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: Work Diary

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: Model Diaries For Schoolgirls

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: New Citizen’s Fountain Pen

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: Red Star Diary

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: A Record Of Achievement

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: People’s Diary

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: The Age Of Greatness

- ⧉Image Personal Diaries: Sun Yat-sen Suit / Mao Suit

Geography

Chongqing was the wartime (1937-1945) capital of the Republic of China, situated in the western province of Sichuan where it was difficult for Japanese forces to reach. Previously, the city was administered by regional warlords until the Republican government under Chiang Kai-shek began asserting its authority there from 1936. The wartime government changed the city, leaving behind many professionals and educated workers. Those who were local, or chose to remain in Sichuan after the war and 1949 revolution, had to adjust to the new regime very quickly, for which the diary would be a useful tool.

Kunming is the capital city of Yunnan Province, which contains several ethnic minorities and borders Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar, which were European colonies prior to the Japanese invasion in WWII. Kunming had rail and road links to French Indochina prior to WWII, as well as French villas and foreign residents. The city and province were dominated by local warlords, who sided with the Republic of China against Japan in WWII (1937-1945) and although Kunming was bombed, it was never occupied. Warlord Long Yun 龙云 kept Kunming largely independent from Chiang Kai-shek's wartime capital in Chongqing as well, giving the city a unique historical profile. Although Chinese Nationalists and Communists were present in the city and surrounding areas, most educated Chinese people in Kunming had little experience with or knowledge of communism.

Wuxi and its surrounding Jiangsu Province were a stronghold of the Chinese Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek. Many educated workers and professionals lived there and also endured a lengthy Japanese occupation (1937-1945). They had little experience of communism prior to 1949. Wuxi and Jiangsu Province, densely populated, in the Republican Era the people were well educated, and families were wealthier when compared with other provinces of China. Consequently, many educated Chinese residents of Wuxi and Jiangsu, especially those whose families engaged in landlordism, had to be careful with their actions and speech under the new regime.

Nanjing was the capital of the Republic of China from 1927, following the conclusion of the Nationalist Party's Northern Expedition (1926-1928) to defeat Chinese warlords and establish national unity. Consequently, the period 1927 to 1937, when the Empire of Japan occupied the city, is referred to as the 'Nanjing Decade'. Under Chiang Kai-shek's rule, the capital was redesigned and hosted foreign residents, highly skilled researchers, financiers and businessmen, and a large number of educated workers and professionals. After 1949, the residents of Nanjing had to be extremely cautious about their actions and speech, as they were living in the capital city of the regime that had directly opposed the Chinese Communist Party.

Timeline

Further Reading

Brown, Jeremy and Matthew D. Johnson (eds.). Maoism at the Grassroots: Everyday Life in China’s Era of High Socialism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Dryburgh, Marjorie and Sarah Dauncey (eds.). Writing Lives in China, 1600-2010: Histories of the Elusive Self. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Hellbeck, Jochen. Revolution on My Mind: Writing a Diary under Stalin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Kiely, Jan. The Compelling Ideal: Thought Reform and the Prison in China, 1901-1956. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

Schoenhals, Michael and Richard King. ‘The Cultural Revolutionary “Public Diary”’, CCP Research Newsletter no. 3 (1989): 18-22. PRC History (prchistory.org/ccprn).

Smith, Aminda M. Thought Reform and China’s Dangerous Classes: Reeducation, Resistance, and the People. Rowman & Littlefield, 2013.

Summerfield, Penny. Histories of the Self: Personal Narratives and Historical Practice. London: Routledge, 2019.